Noria Research is an independent research center dedicated to the production, promotion and dissemination of field research in international politics

Call for grants

The call for applications for the 2025-2026 grants is closed!

Our Research Programs

Latest publications

-

Middle East & North Africa

From al-Assad to al-Shara’a: Technocratic and Banking Networks Behind Syria’s Financialization

-

Middle East & North Africa

Temporalities of Crisis: Egypt Today and Tomorrow

-

Africas

Archives et éthique de la recherche en histoire de l’Afrique : retour d’expériences sur différents terrains ouest-africains

-

Middle East & North Africa

Gaza’s Reconstruction and the Settler-Colonial Logic of Elimination

-

Middle East & North Africa

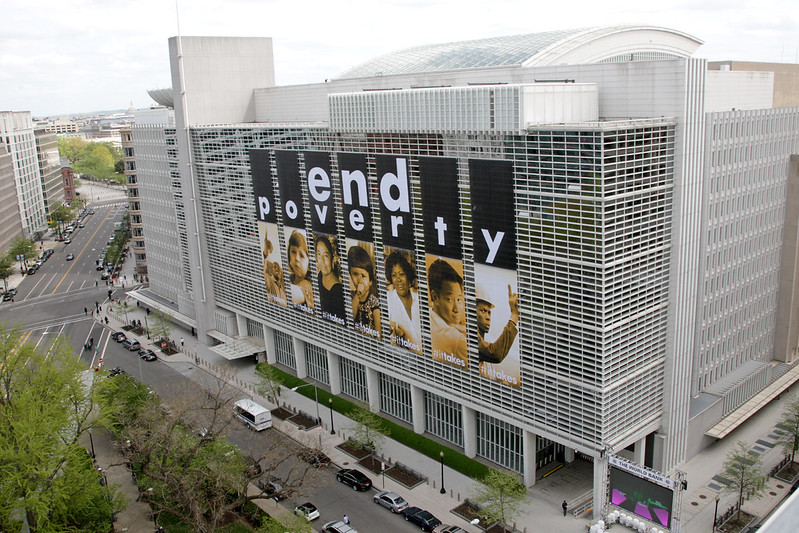

The Debts Haunting the Future of the Global South

Join the team

Researcher or student ?

Take part in our activities and programs

Write for us

Publish your research